Fridays are the day to wear “African print” outfits in Ghanaian offices, yet some designers are boycotting such fabrics – arguing they are not actually African.

The history behind the designs is complex – and involves several continents.

Office workers Joseph Appiah-Dolphyne and Karen Dodoo are shocked to discover the provenance of the popular prints they wear.

The two business journalists at Adom News were decked out in similar outfits when I visited their office one Friday in the capital Accra – though hers was purple and his green.

The pair had not co-ordinated their wardrobes, yet weren’t surprised by the coincidence.

They told me that the circular design was called “subura” which means “water well” in English and is one of the most popular patterns in Ghana.

“When you go downtown on a Friday you meet a lot of people with the same pattern,” Mr Appiah-Dolphyne said.

He was right. Walking through Accra’s Makola market, it seemed as though every other person who walked past was wearing it – like baker Gloria Assagba, who had designed her own trouser suit.

The government’s campaign to get people into national dress on Fridays started in 2004 to support the local textile industry, yet a lot of the fabric worn is not made by African firms.

Ms Dodoo’s fabric, for example, was made by Chinese brand Hitarget.

She said she clubbed together with others to buy it: “We chose the Chinese fabric because 12 of us from church were all getting the same outfit and it was cheaper.”

Mr Appiah-Dolphyne bought his fabric from Ghana Textiles Printing (GTP), which, despite its name, is owned by Dutch company Vlisco – which also designed the print.

He was shocked when I told him that it was Dutchman Piet Snel who had created it in 1936 for Vlisco.

“It was designed in Europe? That’s news to me. I thought it was designed in Ghana. It’s sad to hear. We can easily design clothes, so why not do it?”

These sentiments are shared by Ghanaian designer Nana Kwame Adusei.

He refuses to use African wax prints, as they are known, for his ready-to-wear clothing brand Ćharlotte Prive, saying they are a legacy of colonialism.

“The wax print companies have been making money for 170 years and the money doesn’t come back to us.”

This has also put off Nigerian Amaka Osakwe from using them in her fashion label Maki Oh while Malian-born indigo dyer Aboubakar Fofana has said he could “never agree with the use of wax print to symbolise African-ness”.

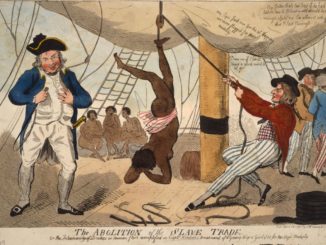

What these designers are touching on is the intriguing history of wax print dating back to the Napoleonic wars in what is now Indonesia – and the local, hand-made method of making batiks.

This laborious process was recorded in detail by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, governor of what was Java in 1811 when the British captured the island from the Dutch.

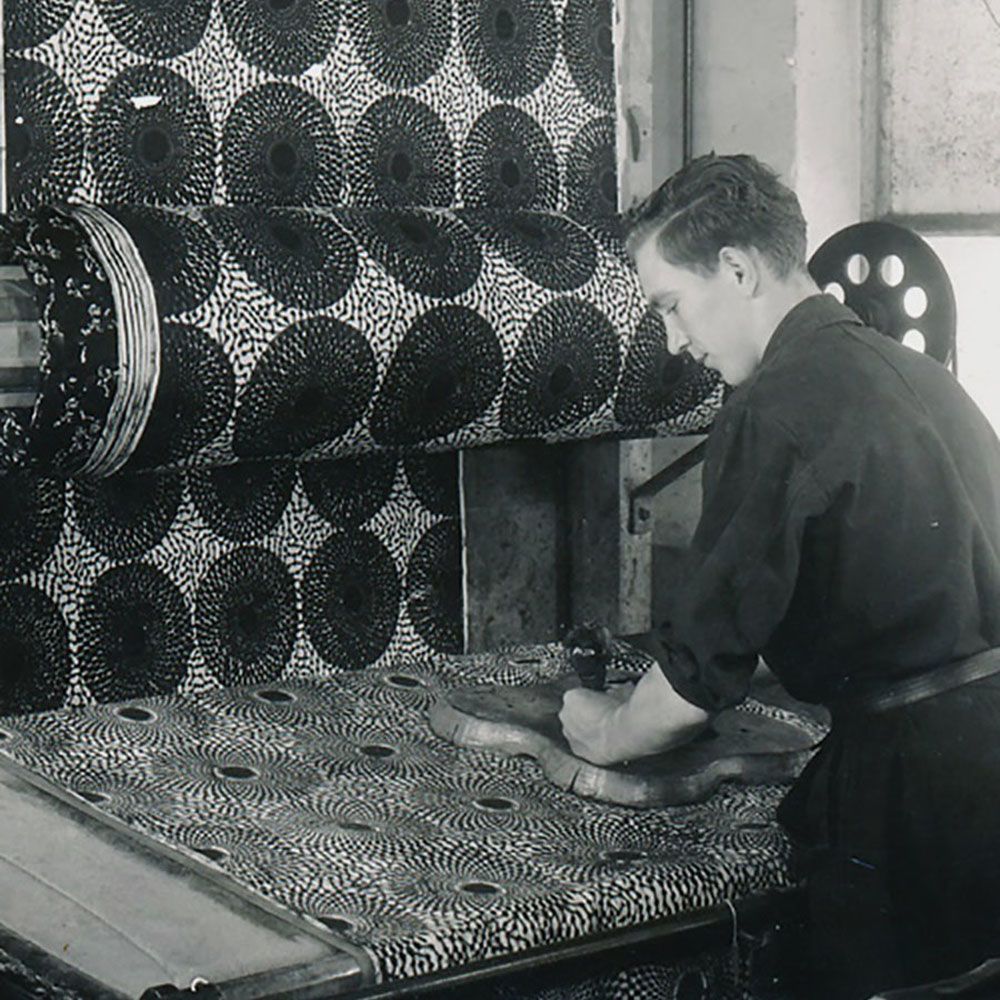

He explained how hot wax was passed through a tube to draw designs on to fabric which was dyed and then re-waxed and dyed again for up to 17 days.

“He then sent 22 pieces of Indonesian batik back to England with a challenge to the men of industry to find a way to mechanise it,” explains documentary maker Aiwan Obinyan, who traced the history of the print in the film Wax Print.

A peace treaty returned Java to the Netherlands and Raffles left. But the Dutch could also use his book to help work out how to mechanise the process so they could undercut expensive hand-made batiks.

And in the end the Dutch won the race against the British.

The first batch of machine-made batiks was exported from Holland to the Dutch East Indies in around 1850, writes anthropologist Anne Grosfilley in African Wax Print Textiles.

But it was a flop and the fabric sold at a loss.

–

Source: BBC