I read with some level of disquiet the report in the Guardian newspaper of November 5, 2018, of the visit of a member of the British royal family, Prince Charles, and his wife Camilla, to Ghana, a country from which millions of Africans were captured and forcefully relocated to the Americas in European slavers, including many from the UK, to endure a life of terror on plantations and other enterprises.

In his speech delivered at the Accra International Convention Centre, the prince touched on topics like Ghana’s role in the European Civil Wars (called World Wars 1 & 2), the Commonwealth and its future, the contributions that an estimated 250,000 Ghanaians are making to UK society, climate change and the benevolence of the United Kingdom, which “has been helping to make a difference in Ghana, whether through the private, government or NGO sectors”.

At Christiansborg Castle in Osu, which originally operated as a Danish ‘slave trade fort’ (but not at sites where British atrocities were carried out), as well as at the Convention Centre, the prince confronted Britain’s role in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans.

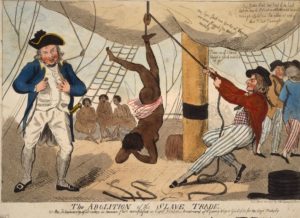

My disquiet was related to the fact that while the heir to the British throne acknowledged that Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans was an appalling atrocity that has left an “indelible stain” on the world, like all other British officials who have issued comments on Britain’s culpability in the Ma’angamizi (African holocaust), he stopped short of issuing an apology to the people of Ghana and the sites of Britain’s plantation slavery in the Americas.

An apology would have demonstrated to the world that a penitent nation admits to this crime against humanity, commits to repairing the damage done by the crime and to non-repetition. Furthermore, and like others before him, he failed to acknowledge that Haiti and the Danes were ahead of Britain in taking steps to end the historic trafficking in Africans (and in Haiti’s case, slavery), instead erroneously claiming that “Britain … later led the way in the abolition of this shameful trade”.

That no apology was proffered or reparation discussed by a member of the British royal family is even more troubling, given the fact that royal families throughout Europe developed financial interests in the trade, and monarchs from King Louis XVI of France, King George I of England, King Christian IV of Denmark, and King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden had mutual interest in the trade’s prosperity.

Exclusive Licences

State-sponsored companies, from Portugal’s Cacheu, Maranhoa, and Pernambuco Companies to Holland’s West India Company, and Britain’s Royal Adventurers, Royal African Company and South Sea Company, were granted exclusive licences to operate in the trans-shipment of millions of Africans. With royal patronage, and the need to ensure a return on investment, the level of organisation that went into the capture and subsequent enslavement of Africans was unmatched.

It is high time that the UK move beyond platitudes in the tradition of similar statements by their former prime ministers, Tony Blair and David Cameron, and their minister of state for the Commonwealth and United Nations, Tariq Ahmad, live up to its responsibilities and pay reparation to those disfigured by its involvement in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and plantation slavery.

By Prince Charles’ own admission, “the appalling atrocity of the slave trade, and the unimaginable suffering it caused, left an indelible stain on the history of our world”. It is time to remove that stain.

As Sir Ellis Clarke, the Trinidad and Tobago’s government UN representative to a subcommittee of the Committee on Colonialism said in 1964, “An administering power … is not entitled to extract for centuries all that can be got out of a colony, and when that has been done, to relieve itself of its obligations … . Justice requires that reparation be made to the country that has suffered the ravages of colonialism before that country is expected to face up to the problems and difficulties that will inevitably beset it upon independence.”

–

Verene A. Shepherd is a social historian and chairperson of the National Commission on Reparations. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and reparation.research@uwimona.edu.jm.

Credit: jamaica-gleaner.com